Alexander Verbeek

I like creating. I love gaming. Creating games is my passion.

On the Level Design in iO

November 10, 2015

Just a few weeks ago, a new update to iO was released, which added a whole bunch of new levels! There’s also a new trailer:

In light of that event, I thought it was time to write another post about the development process of iO. Occasionally I’ll get questions from people on the thought process behind these levels. So this time I’ll be talking about the subject of level design.

Intro

Let me first start with a small disclaimer. Most of the levels in the game were not designed by myself. I was very heavily involved in the game design prototyping in early stages of development of the game, and later on I was pretty much The Programmer Guy whose task was getting the thing to work smoothly and without bugs on all platforms. As a result I did not spend much time on the levels themselves in the later stages of development. That said. I do believe I laid a lot of the conceptual ground work for some of the most interesting levels currently in the game.

Note also, that the process I describe here may not be suitable for all games or developers. This is simply what worked for me, on this project.

Before I delve in the process of level design itself, bear with me as I want to discuss a very important and related concept, which is:

Emergent Game Mechanics

One of the most difficult aspects of level design I found is not the actual physical design (line drawing, obstacle placing etc.) of levels but instead the conceptual design. To make a good level, you want to keep asking yourself the question; How can I create a new and interesting experience with the mechanics that I already have?

After my first experience creating a few dozen levels which I felt were very unsatisfying, (And none of which ever made it into the game) I realized that I needed some structured process for creating levels, and stumbled on a concept that I already knew about but didn’t think applied to this game.

Emergent Game Mechanics arise not because a programmer explicitly coded them into the game rules, but from the interaction of several already existing game mechanics. Emergence is a frequent occurrence in games with a lot of procedural generation and in games where the player has a large amount of creative freedom. (Dwarf Fortress is a prime example, and an awesome game. Don’t let the interface scare you. It’s easier to play than it looks at first glance!)

Unfortunately our game iO is not based around procedural generation, nor does the player have lots creative freedom. Our game is level based and each level is handcrafted. Levels are more like a puzzle or a race, than a sandbox. This means we cannot rely on spontaneous emergence. We have to actively do work to discover the hidden potential in our game and bring it to the surface with smart level design.

The best way to do this is to get to know the implications of your game rules and their implementation as intimately as possible. It’s not enough to simply know the game mechanics and how you implemented them. You also need to think and analyze all the different ways in which they might interact. You might find that some of your rules would normally never get a chance to interact unless there is a set of very specific conditions. If you can figure out what those conditions are, then you can build your level design around it, to try and make a new interesting experience using that derived mechanic.

Concept Levels

So how do we turn all that theory into proper levels? Well. If you are really delving deep into your game, living and breathing it daily, then your best ideas might occur in the shower or on the bus. All these problems will float through your head until, at some random moment, your subconscious presents you with a solution which you might experience as a flash of inspiration. So it is important to always keep a little notepad or booklet to write on somewhere nearby. More low-tech, the better. You can then quickly make a sketch of the idea before you forget about it and save it for later when you have time to work on it. This way you might collect a dozen sketches in a week.

The next step is to turn such a sketch of your idea into a more detailed sketch. This is where you might do the first estimates on the dimensions of various elements in a level and how elements are aligned or offset from each other, in order to make the idea work.

Then you turn the sketch into a concept level, inside the game. A concept level is a very small level which contains only the bare essentials to demonstrate the concept of this new mechanic. Nothing more, nothing less. It will serve as a proof of concept, so it is important that you are able to test the idea by playing the level inside your game or game editor.

Once you demonstrated the feasibility of the mechanic with a concrete concept level, you can then start integrating similar structures and challenges in other levels. You can even use many concept levels as introduction levels where a new mechanic is introduced without other distracting context. Or you can again combine various concepts together into new bigger levels.

Ideally, combining already existing mechanics to create new mechanics in this way should allow you to create a ton of new content without writing a single line of code or creating new assets. (other than level geometry) In reality, you may still need to do a few small tweaks here and there. Maybe to adjust some friction value, perhaps to change a mechanic’s implementation ever so slightly to allow the two to combine smoothly. Things like that.

Examples

Of course, combining existing mechanics to create new ones requires you to already have at least a few of them. If your core mechanics are not yet fleshed out, then you need to take a step back and work on that first. Otherwise you’ll be putting the cart before the horse.

From the very start (a 48 hour game jam prototype) our game contained the following mechanics:

- Rotating player ball. Can apply torque to left and right to roll, and can grow or shrink in size.

- Blue lines are simply solid. They are much like tiles or platforms in other games.

- Yellow objects are rigidbody objects.

- Red lines will kill the player upon touching them.

- Dark blue objects move by themselves. Think moving platforms and such.

(Both the player and all yellow rigidbody objects are simulated by the physics engine built into Unity)

Here I will show a few old screenshots of levels I created, to illustrate how elements that already exist in a game can be combined into new experiences:

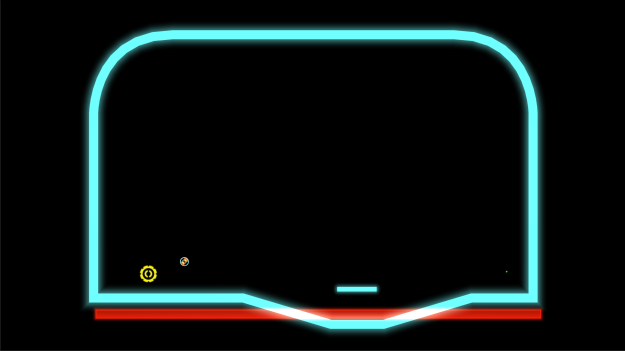

Bearings

We already had a rolling player character. And we already had some yellow rigid body objects from another level with balancing bars and a pile of blocks. Rearrange them in a specific position, and add a few constraints, and you have something resembling sliding doors, which the player can open by rolling to one side, when he is on the yellow bars.

We already had a rolling player character. And we already had some yellow rigid body objects from another level with balancing bars and a pile of blocks. Rearrange them in a specific position, and add a few constraints, and you have something resembling sliding doors, which the player can open by rolling to one side, when he is on the yellow bars.

It’s not a challenging or especially interesting level. But it’s definitely an ‘Aha!’ moment for the player in the very early game.

This level is very similar in shape to an earlier level where the player learned to first shrink and then grow to get through the gap on the right before preventing himself from falling back down.

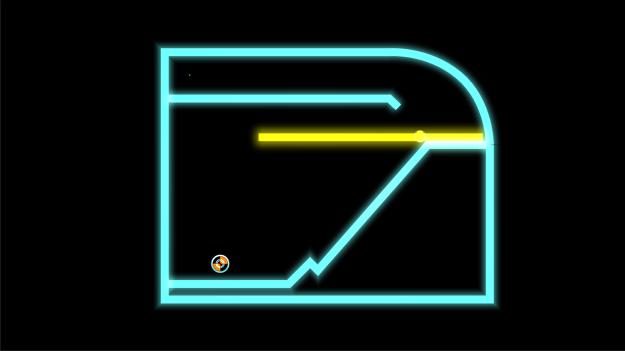

Vehicle

Since constraints worked well last time. Why not take it one step further, and also combine it with the red lines. We’ll construct a vehicle out of the yellow objects, and use that vehicle to traverse the red death line.

This vehicle idea spawned an entire new type of levels. Methods to get into or out of the vehicle (which can be tricky) and levels where you have your vehicle go places where you can’t go before meeting up with it and getting back in to continue.

This vehicle idea spawned an entire new type of levels. Methods to get into or out of the vehicle (which can be tricky) and levels where you have your vehicle go places where you can’t go before meeting up with it and getting back in to continue.

This level in the game is almost identical to the concept level that I used to prove to myself that this vehicle would actually work and was not just some crazy idea. The red elements are intended to force the use of the vehicle, since it is the only way to get to the bottom side safely. The only changes from the original concept level are the addition of the lip to make it easier to get into the vehicle and the bar at the end to force the player to get out of the vehicle to reach the exit.

Eventually I made a simpler (but much more challenging) variant of the vehicle concept:

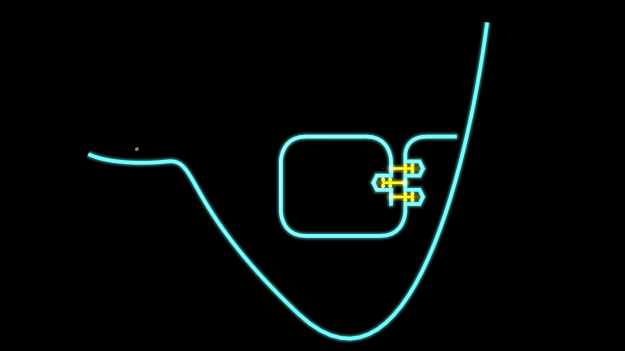

Unicycle

A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. Antoine de Saint-Exupery

In this example, the intent is for the player to balance on top of the wheel to drive it to the other side without touching the red bar. Operating this ‘vehicle’ is significantly more challenging, because you are constantly adjusting your balance, while the other vehicle simply requires you to sit in the middle and provide torque.

Adding a simple bar makes instantly makes the level even more challenging, because you now need to leave the vehicle by getting on the blue bar and then getting back on when the vehicle has rolled to the right side.

Adding a simple bar makes instantly makes the level even more challenging, because you now need to leave the vehicle by getting on the blue bar and then getting back on when the vehicle has rolled to the right side.

Players have found another quicker way to reach the exit in this level, using a brute force trick to jump the gaps from left to right. By fast moving to the right at max size, followed by shrinking to catch the bar and then repeating the process, it is possible to reach the other side without using the vehicle. Using this trick ironically makes this level easier than the one previously mentioned, but only for skilled players.

Sidenote: Having multiple ways to solve a puzzle or overcome a challenge is usually a good thing because it makes it less likely that the player will get stuck, and players might even feel clever for thinking that they outsmarted the game or its creators.

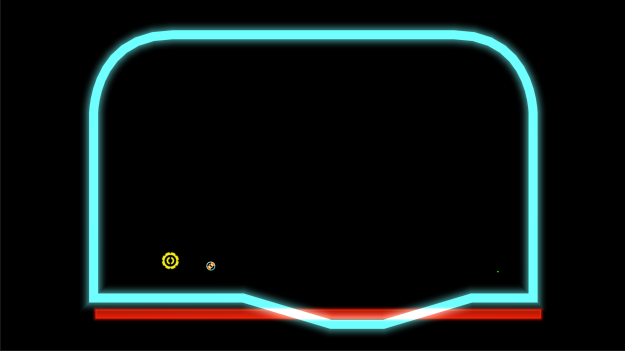

Leverage

Another example where a few simple elements can create an interesting problem. Simply a yellow rigidbody bar attached to a constraint. Note the peculiar shape of the blue lines though. The entire shape of this level was built to support a mechanic that might otherwise never get used.

The idea here the concept of leverage. The yellow bar tilts to the left as soon as the level starts, because its own weight pulls it down. The player rolls onto the yellow bar until reaching the end, then grows in size to increase his weight, which tilts the bar back to the right. The player then shrinks to reduce his weight, causing the bar to fall back down, which causes the bar on the right side of the hinge to rise, throwing the player towards the exit in the top left.

Conclusion

The concept of emergent game mechanics can be a very powerful tool in level design. But it requires you to have a very good understanding of your basic game mechanics, to spot new ways to combine them in interesting ways. I find that interesting level design is in large part a constant search to discover these emergent game mechanics.

Once you have a large set of interesting levels, then you can start thinking about higher level and more abstract concepts like the difficulty curve, gating, game flow, etc.

If you liked this post, please help me out and go buy a copy of iO right now. It’s a really fun game. Tell your friends about it!